Charities need to find their climate voice more than ever

Yes, it’s getting hotter all the time, but, according to government research, people are caring less. At the same time, corporations and politicians are variously seeking to distract, lead and mislead the narrative on climate change.

So how can environmental charities find their voice in our cluttered and polarising information landscape?

In this edition of Stories For Social Good, I discuss:

Why it’s harder than ever for charities to cut through on climate messaging in the current media environment

Why climate messaging needs to adapt to engage an increasingly disillusioned public

What the charity sector can learn from political and consumer brand discourse on climate change

Six ways forward for charities to tell better climate stories

Apart from short-lived spikes of news around hottest days, months and years on record, it feels like climate change has fallen off the radar. In a world where our zone is flooded by a barrage of more urgent things to claim our attention, the gradual drip-drip of the growing climate crisis appears to be getting quieter, not louder.

Second-term Trumpism is attention distraction in hyperdrive. It’s hard to find time for climate stories amid the torrent of cataclysmic tariffs, police roughing up senators and the Zelensky Oval Office ambush. Never mind the Musk melodrama.

Even without Trump, it’s hard for climate stories to cut through. Wars rage in Gaza, Iran, Sudan and Ukraine. People all over the world struggle to meet their costs of living. When it comes to charities, people still give more to health, children, religion, animal welfare, disability, and arts, culture, heritage or science than to environmental causes.

Yet, the impacts of climate change continue to be felt more frequently, violently and by more people every year. As I write in early July 2025, recent flash floods in Texas have claimed more than 120 lives, including 27 Camp Mystic campers and counsellors; 684 people have died in European heatwaves; and the Mokwa flood in Nigeria claimed 206 lives. To mention but a few so-called ‘natural disasters’ (there’s no such thing).

Climate change is getting worse, but people are caring less

Climate-related disasters are on the rise, but people are worrying about global warming less. In the UK, in spring 2025, 77% of people were concerned about climate change, down from 85% in autumn 2021. Over the same period, the proportion of people not concerned about climate change grew from 14% to 21%.

If the devastation wrought by rising temperatures is increasingly visible, why are people becoming less worried, not more?

In some respects, we should expect that people have gradually become desensitised to messages about climate change; the environmental movement has been talking about global warming’s irreversible damage to nature, oceans and communities for at least half a century.

But in the last few years, public apathy is turning to active resistance. Not only are fewer people concerned about climate change, but more of us have become opposed to ‘net zero’ (the target for neutralising harmful emissions by 2050). In the last year, support for the UK’s net zero target plummeted from 62% to 46%.

Right-wing populist parties from Trump’s Republicans to Farage’s Reform UK, the AfD in Germany to Italy’s Lega party, argue vociferously that pro-environmental policies damage growth. Climate action has been lumped in with DEI initiatives as further proof of the woke, liberal left’s insistence on ruining all our lives.

As I wrote in last month’s newsletter, social justice charities and purpose-led brands need to change their approach to survive the woke backlash. A similar challenge is coming down the track for climate charities.

Shouting louder may not be the answer

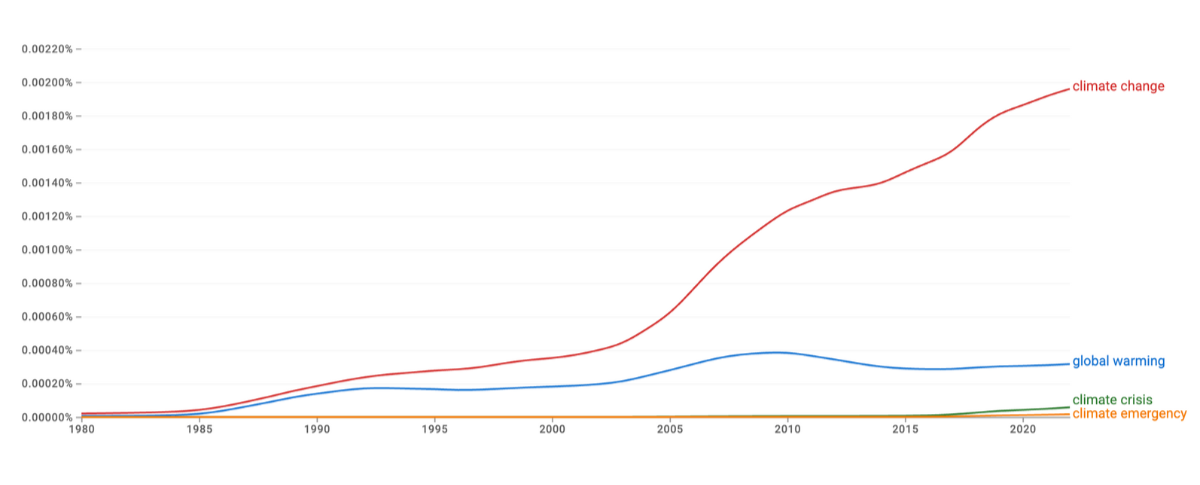

The clue’s in the name. ‘Climate change’ has been around for a while, increasingly preferred to ‘global warming’ as the main shorthand for what happens when greenhouse gas emissions affect our weather, climate and ocean temperatures. But in the last few years ‘climate crisis’ and even ‘climate emergency’ have sprung up to reflect the growing urgency of the situation.

Google Ngram, accessed July 2025, showing how ‘climate change’ has risen in popularity over ‘global warming’ since 1980, with ‘climate crisis’ and ‘climate emergency’ becoming increasingly commonplace since the mid 2010s.

‘Emergency’ is the most urgent. For example, Shelter talks about a ‘housing emergency’ rather than a ‘housing crisis’ because ‘emergency’ demands immediate action, whereas ‘crisis’ may be something ongoing that you can’t necessarily do anything about.

But maybe all of these options miss the point. Perhaps the mere mention of climate is a turn-off, never mind the persistent reminders of how cataclysmic our situation is. It’s not that we’re not in a ‘climate emergency’, but leading with that message may deliver diminishing returns in terms of support for the cause.

Lessons from beyond the sector

I recently collaborated with C Space on The S-Word, their report on consumer attitudes towards sustainability. Speaking to 4,000 people across three continents, C Space researchers discovered that environmental issues have become such catalysts for scepticism, finger-pointing and betrayal that it’s impossible to win hearts and change behaviours with our current approach.

The very fact that a consultancy with C Space’s heft decided to undertake the research speaks volumes about how much sustainability has become a corporate concern. Long gone are the days when corporate sustainability was left to outliers like Patagonia and The Body Shop. Amid rising customer demands, Environmental, Social and Government (ESG) commitments, and the need to stay competitive, for most brands, some degree of sustainability messaging is now baked in.

As C Space found, consumers want brands to show leadership on sustainability with clarity and purpose, without losing sight of customer needs. Life is hard enough without being asked to feel bad, spend more and settle for substandard products and services. Sustainable living should be good living, so brands should focus on benefits, not sacrifices.

A similar message came from the UK Energy Secretary, Ed Miliband, last month, who pointed out that Dr. Martin Luther-King had a dream, not a nightmare. He was pleased that Just Stop Oil has disbanded; it marked a turn away from ‘hair shirt’ environmentalism, the idea that the climate emergency demands extreme tactics (such as throwing paint over high-profile artworks or wearing shirts made of hair). Instead, we should focus on the positive implications of transitioning to green energy, like better jobs, lower energy bills and cleaner air.

The ’hair shirt’ argument is old, but Labour still sees its appeal with mass public audiences. It draws a clear line between an apparently mainstream, ‘common sense’ view and the supposed fringe tactics of activists. Protest charities are responding. @Greenpeace, along with Amnesty International UK, Friends of the Earth and Liberty. have recently joined forces to challenge the government’s new draconian anti-protest laws. Meanwhile, protest movements everywhere are closely monitoring @Greenpeace USA’s potentially existential legal battle with Energy Transfer in an increasingly hostile political environment.

A billboard on a UK high street featuring a black woman with long hair and a placard reading, ‘I’m protesting in here to avoid arrest out there’. The poster has the Greenpeace, Liberty, Amnesty International and Friends of the Earth logos at the bottom.

How can charities find their climate voice?

There are reasons to be optimistic. Fewer people in the UK may be concerned about climate change, but at 77%, they’re still in the overwhelming majority. And Gen-Z and Millennials take environmental breakdown personally, making them more likely to align with organisations that resonate with them.

How do we reach the people who care? Here are six potential ways forward.

Meet the audience where they are. Why will your current and potential supporters engage with you on climate? If they respond to bold, extreme messages, great. If not, find out what they will react to better.

Build long-term relationships. Even the most receptive supporters will get climate fatigue if every message is an emergency demanding urgent action. Consider how your story will keep people engaged over time.

Talk about interconnectedness. If people are gradually engaging less with climate messaging, communicate how climate relates to concerns that may have more purchase. Like these films I scripted for World Wildlife Fund with catalyze about how environmental damage to the Arctic leads to loss of habitats, livelihoods and extreme weather everywhere.

Talk about people. Look for human empathy in climate stories. Like last year’s E.ON and Channel 4 partnership about talking to five-year-olds about climate change.

Get creative. It’s a few years old now, but I love this film lampooning corporate greenwashing from Where From (who seem to have morphed into Really Good Culture).

Stay positive. Of course, some messaging about climate change will have to convey damage and danger. But consider the emotional journey you’re taking your audience on, and make sure you allow room for hope and joy (and even fun) too.

📣 📖 Story of the Month 📖 📣

It might not be the most original choice, but for imagination, impact and coverage, it’s been hard to ignore AI artist Emanuele Morelli’s statement image on ultra-fast fashion. Targeting SHEIN, Morelli’s creativity stops you in your tracks with a vivid visual message about the environmental impact of low-cost consumerism. It also nicely chimed with France’s recent decision to ban fast fashion advertising.

Credit: Emanuelle Morelli.

An AI-generated image of a billboard in the sky showing a young white female fashion model wearing a white blouse. Halfway down, the billboard is cut off to reveal a deluge of scraps of material falling from the woman’s midriff.

Subscribe to the new Stories for Social Good newsletter on LinkedIn ⬇️ and join the conversation. All thoughts welcome in the comments 🙂